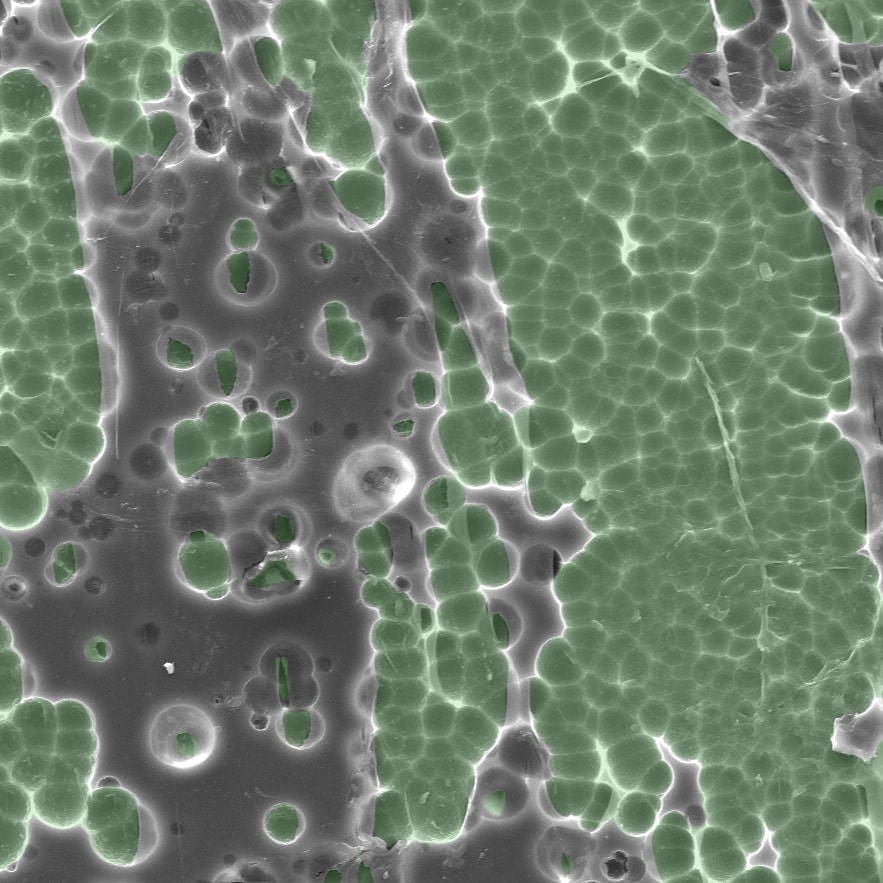

An enzyme which is able to digest some of the most common plastics polluting the environment has been engineered by scientists in the UK and the US.

The research, led by teams at the University of Portsmouth and the US Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), is being suggested as a possible recycling solution for plastic bottles made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) which currently remain in the environment for hundreds of years.

While studying a recently discovered enzyme that digests PET, Professor John McGeehan (pictured) at the University of Portsmouth and Dr Gregg Beckham at NREL inadvertently engineered an enzyme that is even better at degrading the plastic, starting to break down the material in just days. The researchers are now trying to improve it further so it can be used industrially to break down plastics in a matter of hours.

We can all play a significant part in dealing with the plastic problem, but the scientific community who ultimately created these ‘wonder-materials’, must now use all the technology at their disposal to develop real solutions.

McGeehan, who is director of the Institute of Biological and Biomedical Sciences in the School of Biological Sciences at Portsmouth, commented: “Serendipity often plays a significant role in fundamental scientific research and our discovery here is no exception. Although the improvement is modest, this unanticipated discovery suggests that there is room to further improve these enzymes, moving us closer to a recycling solution for the ever-growing mountain of discarded plastics.”

“We can all play a significant part in dealing with the plastic problem, but the scientific community who ultimately created these ‘wonder-materials’, must now use all the technology at their disposal to develop real solutions.”

Professor McGeehan highlighted the possibility that in the coming years there will be an industrially viable process capable of turning PET and other substrates back into their original building blocks so they can be sustainably recycled.

Commenting on the development, Louise Edge, senior oceans campaigner at Greenpeace, said: “It is already possible to recycle PET plastic bottles so what we really need are system changes to reduce the volume of throwaway plastic packaging and make sure plastic drinks bottles are collected and separated effectively. A new enzyme could make the industrial recycling process more efficient, but it can’t reduce the overuse of plastics in the first place or stop packaging getting into the environment.

We have to move away from a throwaway culture where we imagine our waste can magically disappear. Government, business and individuals all need to all take responsibility for the plastic we’re using and discarding, and take steps to change our habits. An enzyme alone can’t clean up the complex and widespread legacy of plastic pollution that we have already created.

“We have to move away from a throwaway culture where we imagine our waste can magically disappear. Government, business and individuals all need to all take responsibility for the plastic we’re using and discarding, and take steps to change our habits. An enzyme alone can’t clean up the complex and widespread legacy of plastic pollution that we have already created.”

Speaking to the BBC today, Sian Sutherland, co-founder of campaign group A Plastic Planet, said that although she was excited about the development, the technology will only help deal with future plastics, not current pollution. “What it won’t help us with is the 6.3 billion tonnes of plastic that exists somewhere on our planet today – in our fields, in our soil, in our oceans. Plastic right now you only downcycle – this whole myth of recycling plastic, of one bottle becoming another bottle, that’s not a reality … Our campaign is saying let us turn off the plastic tap and refocus on food and drink packaging … we don’t really need to package our food and drink that is going to be with us for a matter of days in a material that is such a miracle, it exists forever.”